1812When Napoleon Ventured East

- Napoleon’s main force on the offensive

- Retreat of Napoleon’s remaining troops

Minard mapprologue

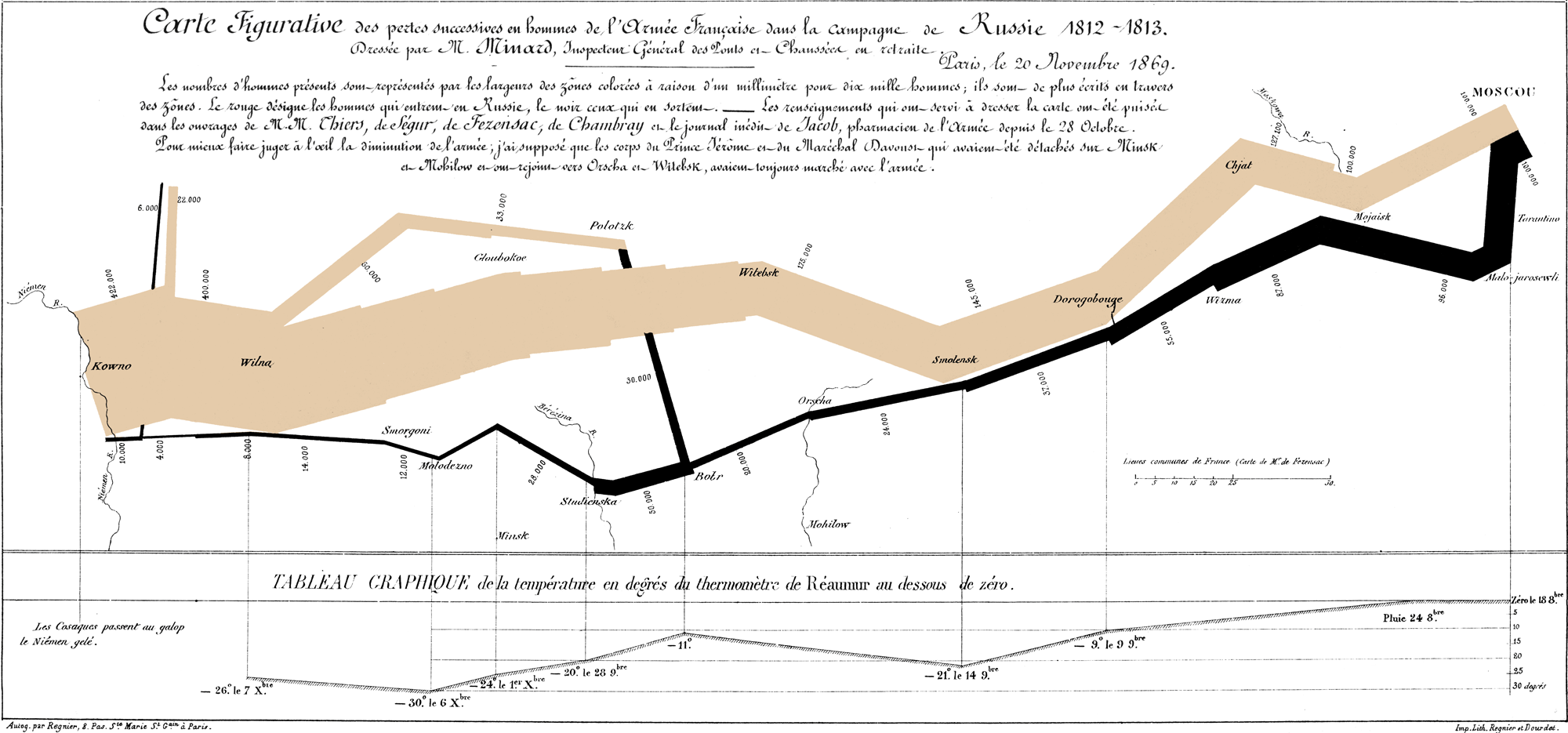

In 1869, retired French civil engineer Charles Joseph Minard summarized eye witness accounts and drew a map illustrating Napoleon’s 1812 campaign against Russia and the defeat of the Grand Army. According to Minard, during the war’s bloody 197 days, the strength of Napoleon’s forces dwindled from 422,000 all the way down to 10,000.

Is it true that in 1812 Napoleon lost 90% of his troops? And if so, how did it happen and why?

Minard lays out some answers to these questions in the form of statistics and line width: tactical errors, hasty decisions, exhausting foot marches, fruitless battles and a brutally severe climate.

We looked into the accuracy of Minard’s statistics and tried to show where exactly the route of the Grand Army lay and to find out what factors resulted in its defeat.

The route of Napoleon’s army is recreated on a modern geographical map. The height columns illustrate the number of troops under Napoleon’s command at different phases of the campaign. The names and boundaries of cities may be different from the historical ones. All dates are according to the Gregorian Calendar (New Style).

- Territory of the French Empire

- Territory of the vassal states and France’s allies

- Territory of the Russian Empire

IFrom the Peace of Tilsit to warmay–june 1812

The war came as no surprise to anyone. Tensions had been simmering since 1810. The differences between Russia and France were not only political but also economic ones. The Russian Empire’s participation in the continental blockade of the British Isles was one of the key terms of the Tilsit Peace Treaty Napoleon and Alexander I concluded in 1807 after the War of the Fourth Coalition. For Russia that meant the loss of important trading partners, while France obtained powerful leverage to put pressure on its main adversary (it was Britain that Napoleon regarded as the greatest obstruction to his drive for European dominance).

In 1810, the Russian Empire legalized trade with the British Empire through mediators, thereby greatly harming the effectiveness of the blockade. Napoleon interpreted that move as a challenge. Both countries launched intensive preparations for war.

At Tilsit, Russia swore to an eternal alliance with France, and war with England. She has openly violated her oath…

Contrary to the widely-spread opinion that Napoleon had no intention of moving Russia’s Western border as far as the Urals. His real intention was to teach Alexander I a lesson, to force a peace treaty upon him advantageous to France and, having acquired support from the Russian army, to launch a military expedition into India (with the aim of reaching British colonies).

Napoleon hoped to pull off the Russian campaign in less than one month. A single large battle near the border some place between Vilno (currently Vilnius) and Vitebsk, he presumed, would decide it all. Apparently, that was his first blunder.

- French forces

- Russian forces

IIFeeling of supremacyjune 1812

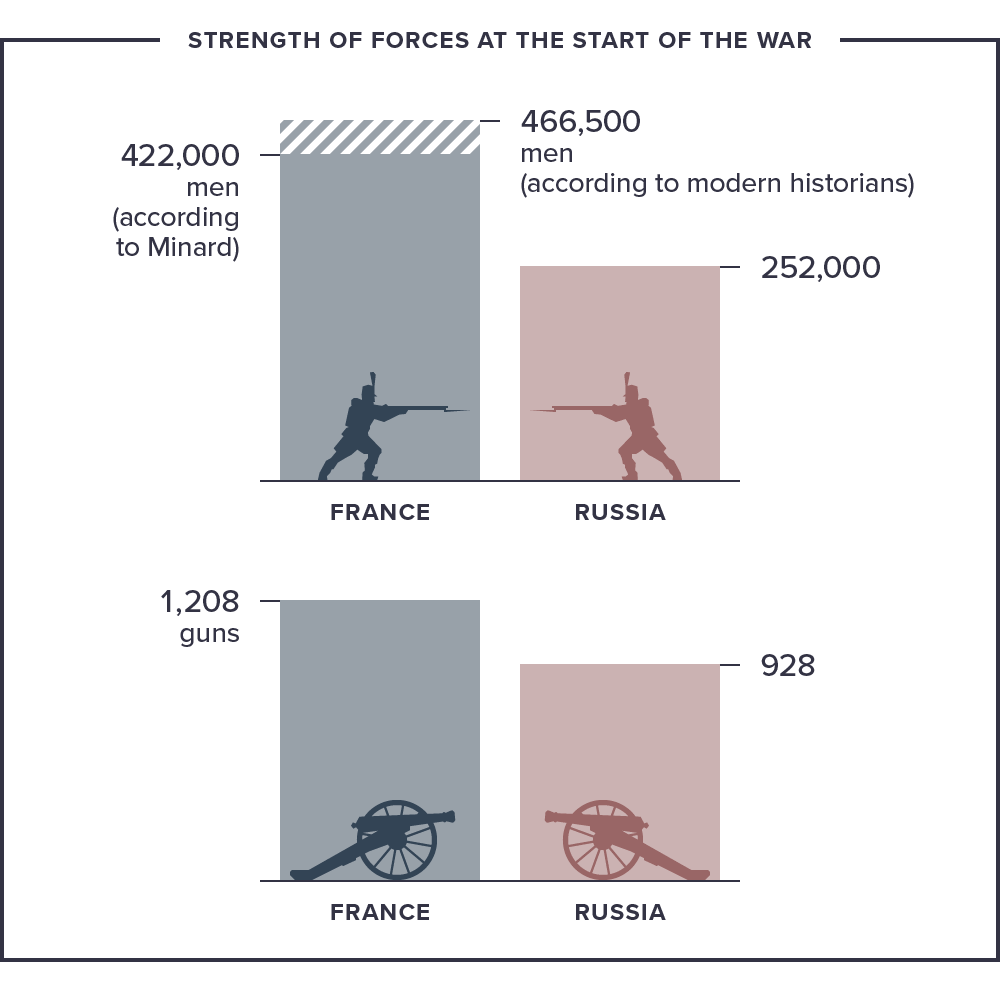

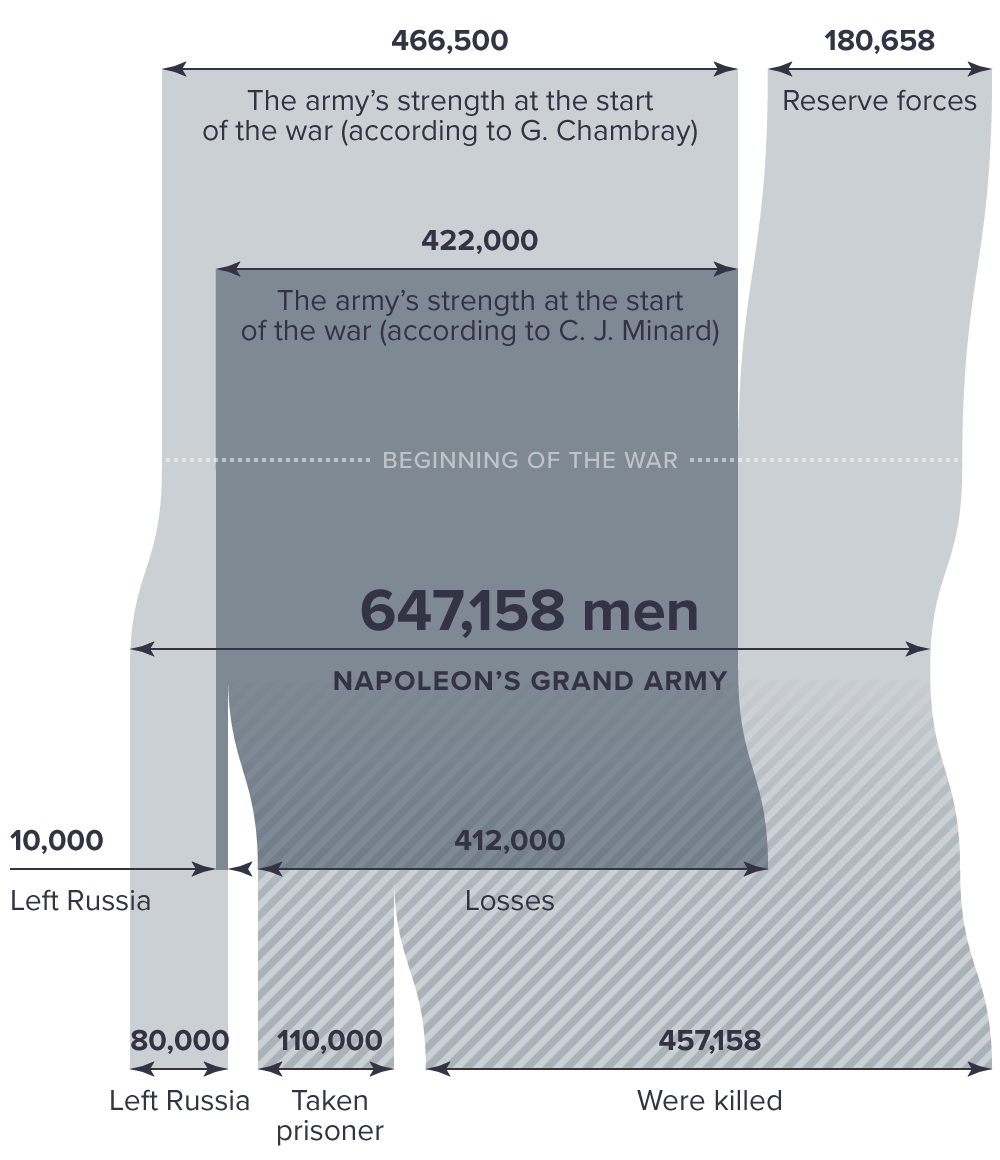

Napoleon’s Grand Army, composed of contingents from virtually all European countries, actually deserved its name. According to Minard, on the eve of the war its strength totaled 422,000. According to modern historians it was even larger: 466,500 men, not including the reserves, and more than 647,000 with the reserves. The Russian Empire’s regular army confronting Napoleon numbered 252,000.

Commands to the Grand Army were issued through Napoleon’s central headquarters. France’s significant numerical superiority was in a sense considerable disadvantage to Napoleon. A huge army was rather hard to supervise. In a situation where all processes depended entirely on just one man, the speed of decision-making left much to be desired. In general, adverse effects hampering the campaign were more than guaranteed.

As for the Russian Empire, at the first phase of the war, Emperor Alexander I personally was in command of all armies. His headquarters were with the 1st Western Army—the target of Napoleon’s main forces.

- Napoleon’s main force on the offensive (column height shows manpower strength)

- Important combat operations and battles

- Important events

IIIThe Neman crossingjune 24, 1812

Oddly enough, the war started precisely where a peace treaty had been signed five years earlier—on the Neman River. On June 24, Napoleon’s forces built several pontoon bridges to start crossing the river. At that moment, the army split up. Several corps headed for St. Petersburg, the southern flank focused on pursuing the 2nd Western Army, while the main forces started moving towards Vilno. Many were very enthusiastic about the beginning campaign. To some it looked like a pleasure trip.

Preceded by the resounding glory of our victories we will venture into this rich and vast country… we see before our mind’s eye universal peace, the conquest of the universe and wonderful heroic glory…

Alexander I received a message about the Neman crossing on June 24 while attending an evening ball at the Zakret countryside manor near Vilno. His manifesto declaring the beginning of war with France was published in the Russian Empire the next day.

IVScythian tacticsjuly 1812

Some say that Napoleon’s military glory did him a great disservice—his contemporaries had enough time to study his tactics in detail. The Russian Empire countered the French Emperor’s reliance on speed and aggressive attack with a so-called Scythian plan—slow retreat deep into the country with the aim of bleeding the enemy forces dry and wearing down their reserves and resources. Whereas Napoleon’s aim was to start the decisive battle as soon as possible, the Russian military tactic was to evade direct collision to the maximum extent.

We will be fighting a prolonged war, for in view of Napoleon’s obvious supremacy in strength and methods this is the sole chance of success that we can count on

Under a prewar plan drawn up by General Karl Phuel (an adviser to Alexander I) the 1st Western army’s final point of retreat was the fortified camp Drissa on the West Dvina river. The force under Barclay de Tolly was to lure in the enemy’s main forces. After that the 2nd Western Army under Prince Bagration would attack Napoleon’s left flank. Upon arrival in that camp, it became clear that it was utterly unsuitable for that purpose.

It is anyone’s guess how the thought of setting up this camp might have ever come into someone’s head; in any case this thought utterly contradicted both the intentions of the commander-in-chief and those of Napoleon himself

Russia’s military strategy needed urgent revision. The military council in Drissa made a decision to continue the retreat and bring the 1st and 2nd armies closer to each other with the aim of their eventual merger. On July 16 the 1st Western army left Drissa.

In the evening of July 18 French troops entered the vacated fortifications. It was only part of Napoleon’s army at the very start of the march on St. Petersburg—the capital of the Russian Empire. The split-up failed to yield the expected results. The units in the north bogged down in prolonged skirmishes and joined the main forces again only during their retreat in November 1812.

During a stop in Polotsk on the same day Alexander I made a decision to create volunteer paramilitary militias. His idea was each nobleman, each cleric and each citizen would take up arms against Napoleon in a joint surge of patriotism. On July 19, Alexander I left the 1st Western Army to start organizing gubernatorial militias in Moscow and St. Petersburg.

In the meantime, Napoleon’s army, though it remained on the offensive, was encountering ever worse problems. The special transport battalions together with their food and fodder convoys were lagging behind the main forces. As some participants in the campaign recall, on the way from Vilno to Vitebsk each regiment had to search for food on its own.

Soldiers used to bring rye or flour but they never managed to get any bread… scouts then set out to find ovens and mills. Since soldiers didn’t have any bread, they put the flour in their soup

Soldiers were suffering from famine, heat, fatiguing foot marches and lack of any results. The Russian army slipped away from Napoleon again and again. The pace of advance slowed down. After taking Vitebsk, the French Emperor was considering in earnest the possibility of pausing the campaign and delaying combat operations till 1813, but the shift in the Russian military strategy caused him to abandon this intention. At last, Napoleon saw a chance of forcing the opponent to fight a large decisive battle.

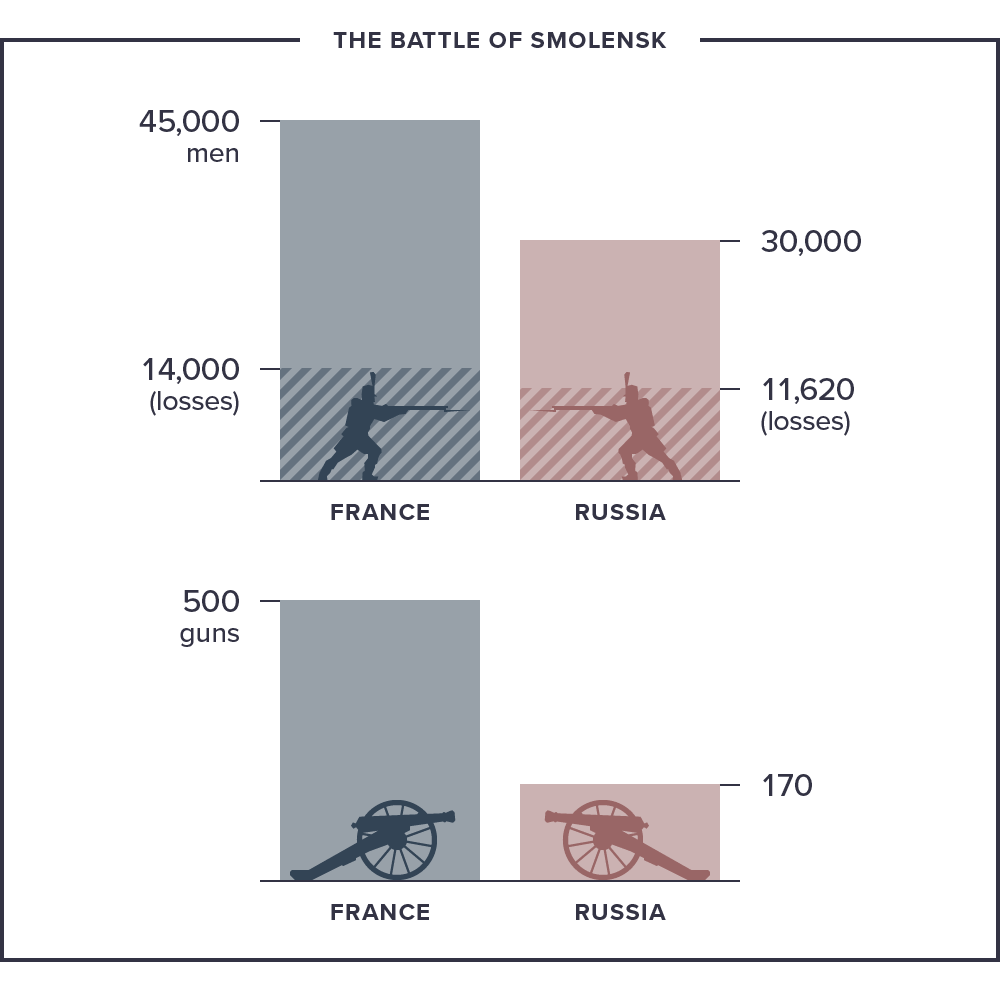

VSmolenskaugust 16–18, 1812

On August 3, the 1st and 2nd western armies joined near Smolensk. Napoleon would have had a chance to stop that from happening, if he had not placed the operation in the hands of his younger brother, King Jerome of Westphalia, but rather had somebody else in command. The troops under King Jerome’s command were expected to beat Bagration’s army, cutting it off from Barclay de Tolly’s forces. However, after stalling for three days in Grodno, that moment of opportunity had slipped through French hands.

As soon as he learned of the operation’s failure, Napoleon tried to correct the mistake by resubordinating the army’s right flank to an experienced commander, Louis Nicolas Davout, nicknamed the Iron Marshal for his long record of victorious battles and stern character. Jerome, feeling insulted by the loss of his original status, left the army for Kassel, the capital of his kingdom.

In the meantime, the main forces of the Grand Army braced for what would turn into the two-day long battle of Smolensk, which would yield nothing but losses. Napoleon failed to implement his plan to promptly seize the city and perform a maneuver that would have blocked any route of retreat for the Russian army leaving them no choice but to enter into an enormous battle.

The Russian generals, too, were unable to cope with the tasks set before them, that is, to turn the tide of the battle and mount a counter-offensive. The enemy’s numerical supremacy was still overwhelming. In the small hours of August 18 the armies under Barclay and Bagration had to leave a ruined Smolensk and continue to retreat deeper into the country.

If you are reading these lines you should know that somebody’s fate has already been decided: either Napoleon has been beaten back or the door to Russia has been unlocked!

During the fierce battle, the city was literally razed to the ground. Out of the town’s 2,250 houses no more than 350 survived the assault. The Russian army was in a depressed mood: everybody was aware that Moscow would be Napoleon’s next target.

VIIn pursuit of the grand battleaugust 1812

The next phase of Napoleon’s campaign can be described with just one word—haste. The march from Smolensk to Gzhatsk (currently Gagarin) was a truly fatiguing experience for the soldiers. Tremendously long supply lines turned out to be a real disaster. Overloaded convoys were hopelessly lagging behind the main forces, which suffered from lack of food and summer heat.

Our horses’ hooves kicked up clouds of scorching sand, fine as dust, which covered us to such a degree that made it hard to tell what color our uniform was. The sand got into our eyes causing agonizing pain. I could barely breathe

“The-army-feeds-itself” principle Napoleon had widely used during the European campaigns did not work on the sparsely populated vast expanses of the Russian Empire. Desertion and marauding became commonplace.

There was no chance for recuperate in the captured cities. The Russian forces strictly followed the orders from Alexander I to “ruin roads, dykes and bridges, destroy mills as well as government-run and private food stores, take away carts, horses and livestock, remove from the archives all sorts of lists, inventories and various statistics and, lastly, to haul away those officials who might give the enemy any information about the territory’s resources and thereby facilitating requisitions to retreat with the army.” The French Emperor had to fight not only with the Russian army, but against the entire nation that rose against him. But Napoleon kept hurrying.

The emperor wanted everybody to fly like a bird

In store for him there lay La Bataille de la Moscowa, which in Russian history is known as the Battle of Borodino.

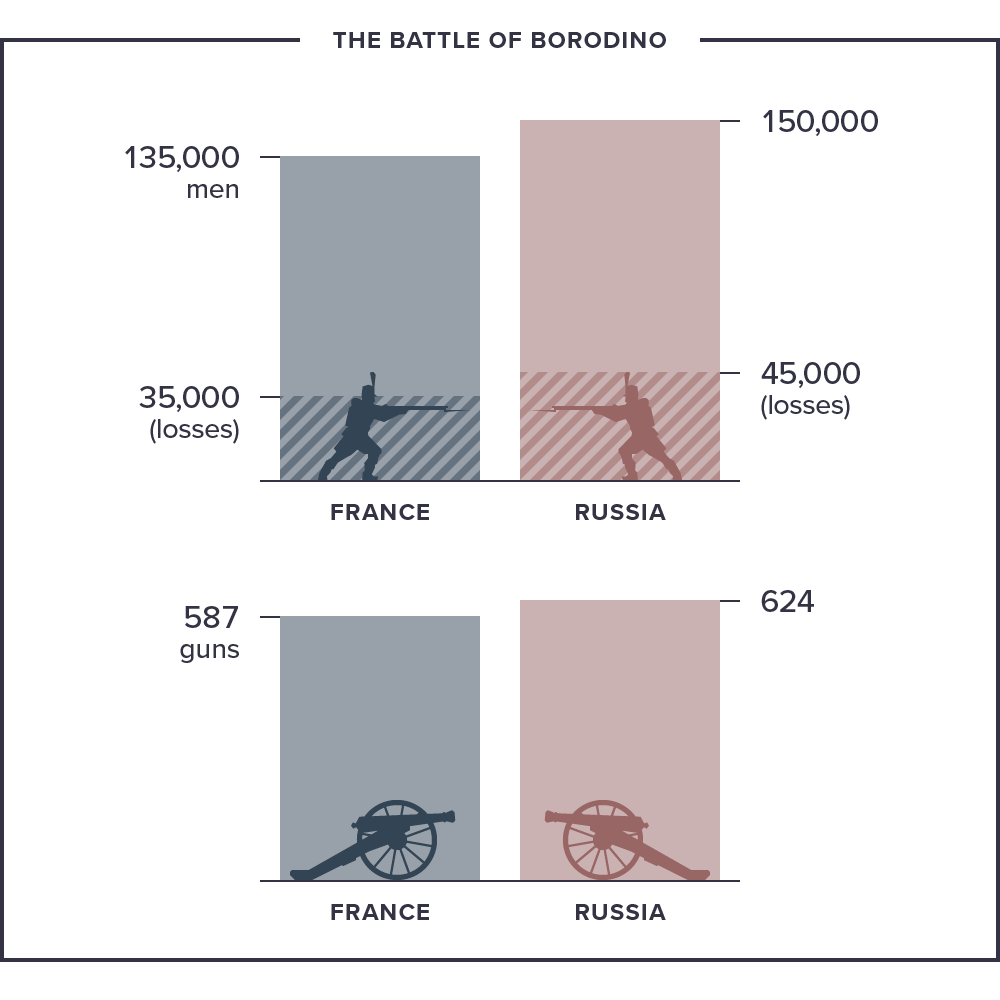

VIIBorodinoseptember 5–7, 1812

The Russian troops’ continued retreat was annoying not only for Napoleon, but also for some Russian generals, too. Many argued the absence of a single commander-in-chief was the root cause of the problem.

Bagration reluctantly agreed with Barclay’s requests because he himself held a conflicting opinion

Alexander I made a decision to appoint to this position Mikhail Golenishchev-Kutuzov, an experienced commander, chief of the St. Petersburg and Moscow paramilitary militias, who just one month before the war with France had clinched a peace treaty with Turkey (thereby securing the Russian Empire’s south-western border). On August 29, Kutuzov took over the command of all Russian armies in the village of Tsaryovo-Zaymishche. The moment of the main battle of the Patriotic War of 1812 was drawing near.

By that time, Napoleon’s army had depleted much of its original strength. About 135,000 men were under his direct command. The Russian Empire's forces numbered 150,000 men (including volunteer militias). Contrary to either side’s expectations, the Battle of Borodino ended in a bloody draw. Napoleon failed to beat the Russian army, while Kutuzov had no chance of stopping the enemy’s thrust towards Moscow.

What a terrible battle there was near Borodino! The french say they fired 60,000 artillery shots and lost 40 generals!

About 2,500 men lost their lives on either side during each hour of the battle. In the end the Grand Army lost about 30,000, including practically all cavalry units. The Russian army lost 40,000 to 50,000 men, including Prince Bagration, who suffered a mortal wound in battle.

No more than 100,000 of Napoleon’s troops reached Mozhaysk, just before the seizure of Moscow. This city is one of the few points on the map where Minard’s statistics agree with the estimates of modern researchers.

VIIIMoscow on fireseptember 14 – october 19, 1812

When the choice is between the army and the city, choose the army. As we know, this is precisely the decision that was made at a meeting of the military council in the village of Fili on September 13. Kutuzov ordered an exodus from Moscow without a fight.

With the loss of Moscow, Russia is not lost yet, but with the loss of the army, Russia will be lost, as well

On September 14, the Russian army concluded a brief ceasefire with the French advanced guard, left the city and moved south along the Ryazan road. A large number of civilians (nearly 200,000 people) followed the departing troops.

Napoleon entered the city on September 15. He was expecting the keys to the Kremlin and a prompt offer for peace talks from Alexander I. Instead, as some participants in the campaign remember it, in Moscow they found “the silence of the desert.” Fires began in the city in the evening of the same day.

- Built-up area

- Built-up area destroyed by fire

- City's boundaries in 1812

In just four days ¾ of the city went up in flames: of the 9,158 residential buildings more than 6,500 were burned to the ground. Napoleon lost the winter housing he had hoped for. Yet the French Emperor retained the illusion that his campaign was close to the expected outcome and that the Russian Empire would sign a peace treaty with him at last. On September 18, he decided to stay in the city and dedicate himself to formulating his “November plan” for a march on St. Petersburg.

In the city center, there is not a single store that has been left untouched except for a book store and another one at the city administration. Resin, vodka, vitriol and the most expensive goods—everything is in flames

While Napoleon was holding show trials of arsonists in Moscow, Kutuzov literally dropped out of sight. The Grand Army’s advance guard under Marshal Joachim Murat was misled by a Cossack regiment, which had orders to retreat as soon as the enemy force tried to come closer, thereby creating an illusion that the Russian army’s main force was moving in the same direction.

For three straight days, Murat thought he was chasing our army, while in reality he had ahead of him just several thousand cossacks, who made camp fires for the night on a large area, ostensibly taken up by a large army; one morning the cossacks just vanished before his eyes and he was left all alone in front of a vacant field

Kutuzov took advantage of the enemy’s confusion to perform the fabulous flank maneuver, which in Russian history studies is commonly referred to as the Tarutino maneuver.

What was the Russian commander-in-chief’s aim when he suddenly led the army off the Ryazan road to the road to Kaluga? Firstly, he blocked Napoleon from the economically unharmed southern provinces of the Russian Empire (including the strategically important weapons plant in Tula). Secondly, he kept under threat the reserves and supply lines of the Grand Army stretching way back to Smolensk. And, the most important aim of all, in this way he hoped to force the enemy out of Moscow. The plan succeeded.

- Retreat of Napoleon’s remaining forces (column height illustrates manpower strength)

- Important combat operations and battles

- Important events

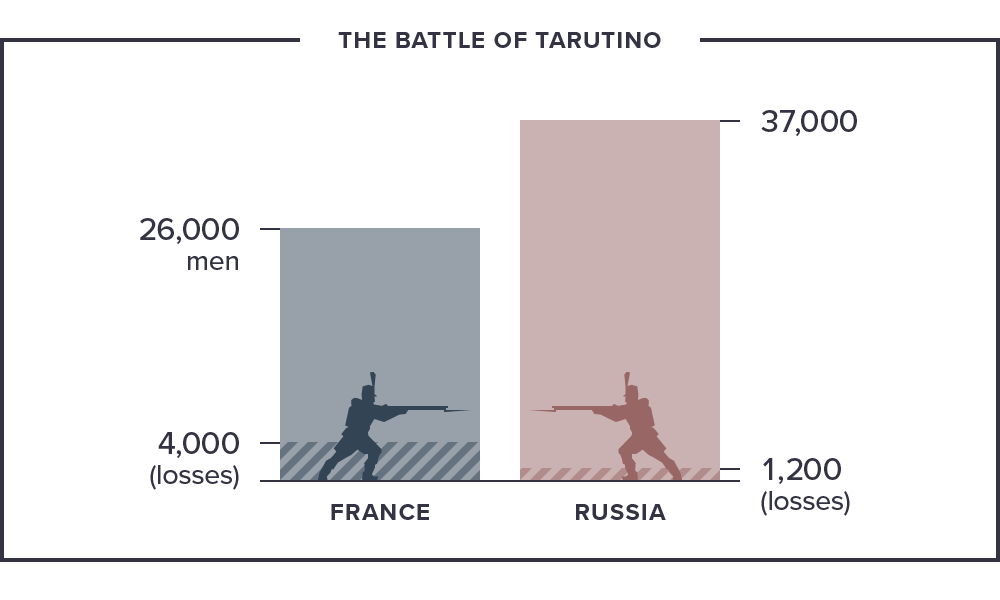

IX“They’ll go just as they came”october–november 1812

Following a failed attempt to enter into peace talks and the Battle of Tarutino, in which the French advanced guard was defeated, Napoleon had to abandon preparations for a march on St. Petersburg and to move towards the Russian army.

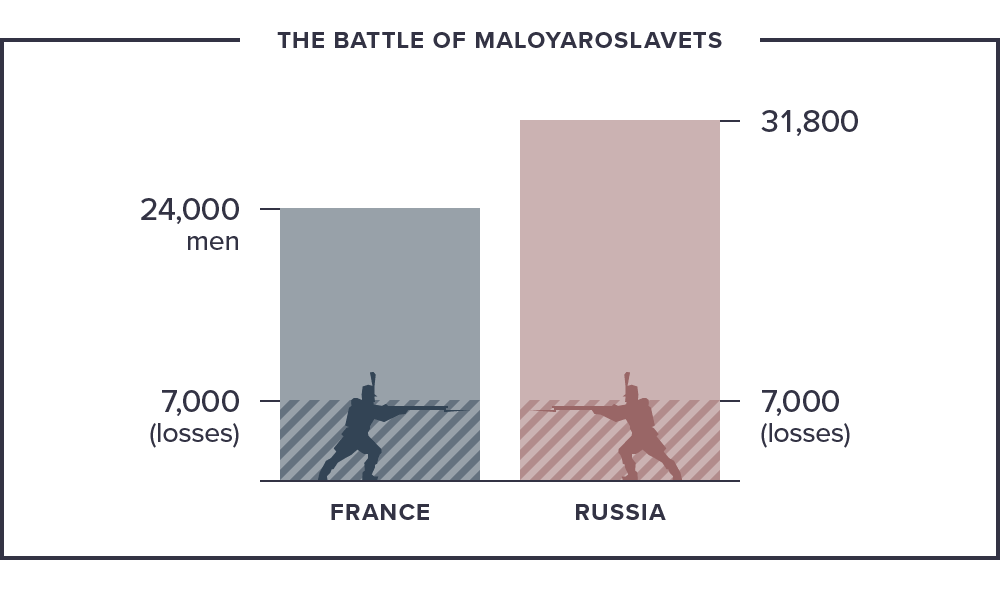

In the meantime, Kutuzov pushed ahead with his own plan. After the battle of Maloyaroslavets, he forced the French army to retreat along the Old Smolensk road through a war-ravaged area. Together with great supply problems, this put the enemy in a very precarious position.

Moreover, when leaving the city, Napoleon narrowly escaped. He was on the verge of being captured by the Cossacks, regarded in the Grand Army as a formidable force. According to the available documents during the 1812 campaign the Cossacks took 50,000 to 70,000 prisoners. The chieftain of the Don Cossacks, Matvey Platov, even promised his daughter would marry the one who would capture the French Emperor.

Undoubtedly, if the emperor had set out, as he had wished, before dawn, he would have found himself in the midst of this swarm of cossacks with only his picket and the eight generals and officers who accompanied him… the emperor would certainly have been killed or captured

The tide of the 1812 campaign had turned, with Kutuzov getting the strategic upper hand. The Russian army launched a counter-offensive.

XWas there a General Frost?november 1812

Previously, the Grand Army had been in pursuit of a grand battle, now it had to defend itself and beat a hasty retreat. The French forces were exposed to blows from all sides. Cossack regiments were on their heels, guerilla detachments were dealing flank blows and the advanced guard was exposed to strikes by peasant militias. On several occasions, Russian troops literally caught up with Napoleon’s rearguard to inflict heavy losses on it. The French were losing battle after battle.

Alongside the never-ending skirmishes with the pursuers, Napoleon had another adversary to contend with—cold weather. The problem began to be felt in Vyazma and took a turn for the worse after the French army had to flee Smolensk so as to avoid being encircled.

Recollections of the time suggest the frosts were not very harsh. According to Denis Davydov (a legendary commander of Russian guerilla units) during the French army’s trek from Moscow to Berezina air temperatures never sank below –17 °С.

Throughout the French army’s march from Moscow to Berezina, in other words, for twenty six days, the bitter frost, though not extraordinary (from –12 °С to –17 °С), lasted for no more than three days, according to Chambray, Jomini and Napoleon, or for five days, according to Gaurgaud

Moreover, in 1807 French troops happened to fight under far worse weather conditions, for instance in a blizzard during the Battle of Preussisch-Eylau in Prussia. “General Frost” then did not inflict any decisive impact on the outcome of the battle. So was its influence on the ending of the French campaign in November 1812 very significant?

The frost during the campaign in Holland in 1795 and the Eylau campaign of 1807 was far stronger than the one that lasted from Moscow to Berezina. But in both those campaigns the troops were getting food, wine and vodka, and had not been trekking in a state of hunger all day long, as it happened in the latest campaign, being certain that tomorrow would be even worse

The history of weather watching, too, confirms that when the French army was on the retreat, the air temperatures were not critically low—on the Minard map they are considerably overstated. For instance, according to the 1812 report by the Vilno Astronomical Observatory, by December 6 the air temperature had dropped to –23 °С, and on the next day to about –25 °С, while the Minard map shows a temperature equivalent to –32.5 °С. In the vicinity of Vilno, the monthly temperature in December averaged –12.2 °С, which is approximately 8.5 degrees below normal.

That Napoleon’s worst enemies were hunger and disorganization is well seen in the condition of the reserve troops, which joined the main forces during the retreat. The troops that before November 1812 had been engaged in the north were not as exhausted as those who had reached Moscow, so the November frosts in no way affected their combat potential. But even after the reserves joined up, the condition of Napoleon’s army kept getting worse day in and day out. After the defeat near Krasnoye, the Grand Army’s retreat quickly turned into a panic flight.

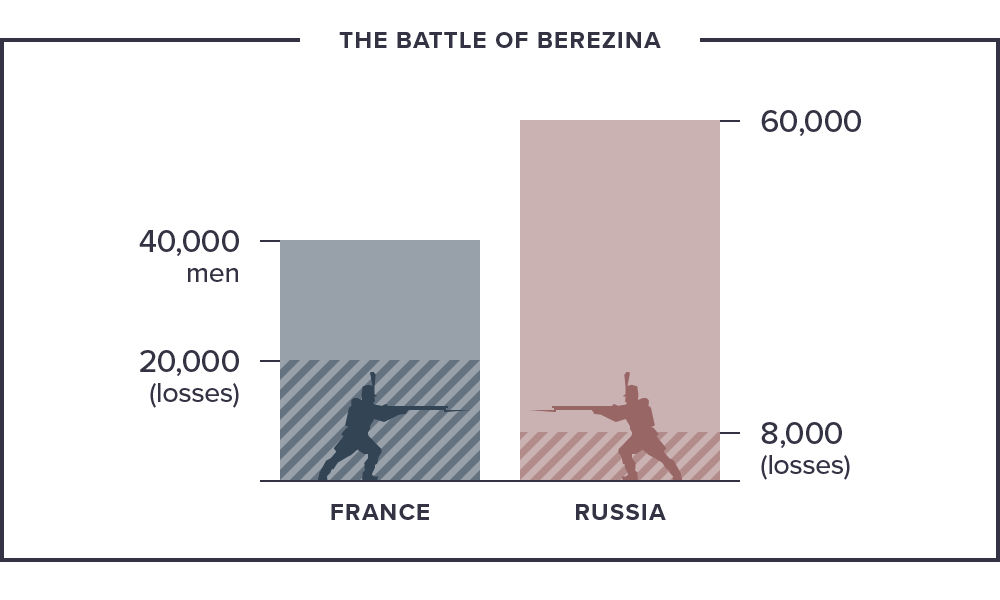

XIThe Berezina river crossingnovember 26–29, 1812

In French the name of the Russian river—Bérézina—is a synonym of disastrous defeat. And in history it is an example of Napoleon’s tactical talent. After the victory in the Battle of Krasnoye, the Russian army was capable of encircling what was left of the French Emperor’s forces and wiping it out. But Napoleon managed to “outwit” the Russian command. Lack of coordination among Russian forces allowed him to buy time to arrange for crossing the Berezina and avoid the complete loss of his army.

According to various sources, the main force of about 19,000 men managed to cross the river in the area of Studenka. Those who remained suffered a dreadful fate. On November 29, Napoleon issued orders to burn the bridges, thus abandoning about 40,000 men—disorganized deserters who fled the combat positions on the Berezina’s left bank. Most of them would soon be taken prisoner or drown while trying to cross the river. The surviving remains of what just recently was the Grand Army headed for Vilno towards the border.

Anything was edible no matter how disgusting it was, it didn’t hold them back from devouring it… sometimes people were gnawing away their own flesh, palms and fingers to quench hunger

XIINapoleon goes to Parisdecember 5, 1812

When Kutuzov was faced with a stark dilemma, he made his choice in favor of the army, and not the city, but Napoleon set his priorities quite differently. On December 3, while staying in Molodechno, he got word of an attempted government coup in Paris, staged by General Malet. On the same day, he decided to leave what was left of his troops, saying the situation being what it was, he would be able “to inspire respect from Europe only from the Tuileries Palace.”

Duke of Istria… openly raised the question to Napoleon about leaving. In his very first words… the latter succumbed to a violent outburst of anger and said that only his mortal foe could’ve suggested he should abandon the army given the condition it was in at the moment… there is proof that the question of leaving had already been settled for him when that scene took place

At 19:30 on December 5, during a stopover in Smorgon, Napoleon delegated the command of the remaining army to King Joachim Murat of Naples, as the person having the highest title. The Emperor ordered Murat to take the troops to Vilno and stop there for the winter.

At 22:00 Napoleon left Smorgon under the name of Duke of Vicenza. He crossed the border on December 7 and by the midnight of December 18, he arrived in the capital of France. As a politician he had no choice. As a military commander, he lost all respect in the eyes of his own soldiers.

The price of ambitionepilogue

Contrary to Napoleon’s orders, the French troops failed to retain Vilno. Under the Russian army’s mounting pressure they had to flee the city, leaving transport, the remaining artillery and the treasury. In the area of Kovno (currently Kaunas) only small group of participants in the Russian campaign crossed the Neman. The war had changed many beyond recognition.

…in Gumbinnen, where i stopped at a doctor’s house as i had done when i had first passed through the town. We had just been served with some excellent coffee when i saw a man wearing a brown coat come in. He had a long beard. His face was black and seemed to be burnt. His eyes were red and glistening. ‘Here i am at last!’ he said. ‘What, general Dumas! Don’t your recognize me?’ ‘No. Who are you?’ ‘I am the rearguard of the Grand Army, marshal Ney.’

Russian troops took Bialystok and Brest-Litovsk (currently Brest) on December 26, 1812 to have completed the liberation of the Russian Empire’s territory. On January 6, 1813 Alexander I issued a manifesto declaring the Patriotic War to be over.

The Russian Empire’s losses totaled about 300,000 (recruitment during wartime included).

As for the Grand Army’s losses, according to the Minard map, Napoleon’s plans cost more than 400,000 lives. Some modern historians argue that the price was still higher—of the 647,000 men who participated in the 1812 campaign no more than 80,000 crossed the Neman back. Another 110,ooo were taken prisoner.

The booklet titled the Retreat of the French, issued by the Russian army’s Headquarters said the Russians crushed Napoleon’s dreams of military expeditions to Persia and India.

The Grand Army is no more

Sources (all in Russian)

- Bezotosny V. M. Russia in Napoleonic Wars 1805–1815

- Beskrovny L. G. Patriotic War of 1812

- Buturlin D. P. A History of Emperor Napoleon’s Invasion of Russia in 1812. Parts 1–2

- Mikhailovsky-Danilevsky A. I. A Description of the Patriotic War of 1812. Third edition. Parts 1–4

- Patriotic War of 1812 and the Liberation Campaign of the Russian army of 1813–1814: an encyclopedia in three volumes

- Podmazo A. A. The Grand European War of 1812–1815. A Chronicle of Events

- Poltoratsky V. A. A Military-Historical Atlas of Wars of 1812–1815 in two volumes

- Onward Move Russia’s Sons: Notes on the Patriotic War of 1812 by its Participants and Witnesses

- Sokolov O. V. Napoleon’s Army

- Troitsky N. A. 1812. Russia’s Great Year

- Works by the Moscow Department of the Imperial Russian Military-Historical Society. Materials on the Patriotic War. V. 4, Part 1

- Vossler H. Under Napoleon’s Eagle at War. Diary (1812–1814) and the memoirs (1828–1829) of the Wuerttemberg lieutenant Heinrich von Vossler

- Frenchmen in Russia: 1812 as Remembered by Foreign Contemporaries: in three volumes

- Kharkevich V. I. The 1812 War: From Neman to Smolensk

TASS expresses its acknowledgements to historian Aleksandr Valkovich, the president of the international military-historical association.

- Text: Kristina Nedkova, Sabina Vakhitova.

- Illustrations: Leonid Mizinov.

- Cartographic data: Anastasiya Zotova, Gleb Trzhemetsky.

- Art Director & Developer: Anton Mizinov.

- Head of studio: Alexey Novichkov.

Translated by Andrey Starkov, edited by Phil Aghion.

Image used courtesy of: Bibliothèque nationale de France (edited by TASS Infographics studio).

© TASS, 2017